Return to Contents | Previous | Next

To understand the changes needed now, it is important to understand where the system has come from. New Zealand was one of the first countries to establish a comprehensive social security system following the major disruptions arising from World War I and the Great Depression in the 1930s. The Social Security Act 1938[2], introduced by the first Labour Government, was seen as taking a world-leading approach. It provided a wide-ranging set of protections against loss of income due to unemployment, sickness or disability, in addition to the existing benefits. It was later accompanied by the universal Family Benefit for each child. Housing was provided through a large-scale state housing programme and subsidised mortgages for home-buyers. The 1938 Act and the subsequent Social Security Act 1964 fitted the social norms and labour market circumstances of the time, high male employment, low labour force participation by married women, a ‘family wage’ approach to wage setting, and a low rate of sole parenthood (Belgrave, 2012; Blaiklock et al, 2002).

From the 1970s, both social and economic circumstances began to change dramatically in ways that the social security system struggled to cope with. Divorce rates and the numbers of sole parents began to rise. In 1972, the Domestic Purposes Benefit was introduced to provide statutory support for sole parents caring for dependent children or other family members. At the same time, women’s labour force participation rose dramatically as women chose to continue their careers after marriage and parenthood. Economically, New Zealand lost its privileged trading relationship with Britain that had underpinned the welfare system and provided near-continuous real wage growth. “Export revenues became insufficient for a growing population and volatile commodity markets highlighted the vulnerabilities of a narrow economic base” (Conway, 2018: 40). This, and oil-price shocks, led to a stalling in real wage growth, contributed to the unravelling of the old wage-setting system, and contributed to rising numbers of unemployed and declining living standards relative to other OECD countries.

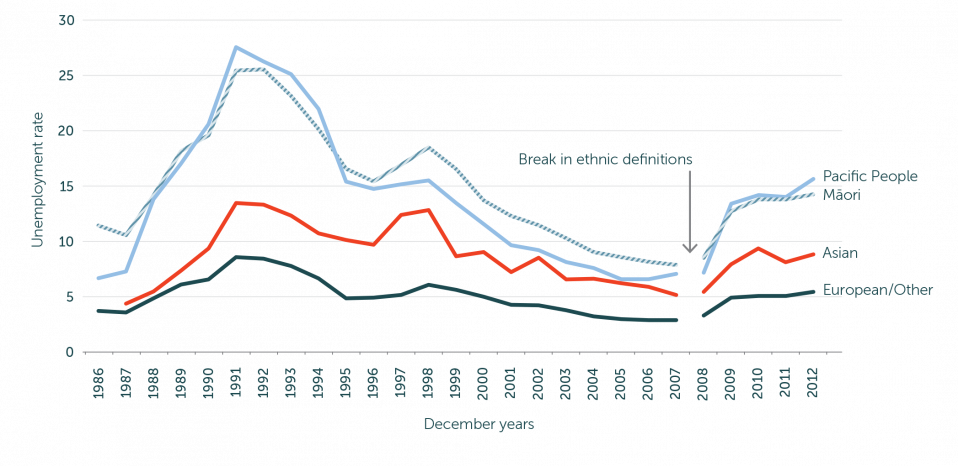

The economic reforms from the mid-1980s to the mid-1990s, intended to adapt the country to the new circumstances through a focus on deregulation and market efficiency, led to a rapid rise in unemployment and benefit numbers further straining the welfare system. In 1981, the unemployment rate[3] was only 3.9% but it reached a peak of 10.6% in 1991[4] and 1992, with 180,400 people unemployed in 1992. The unemployment rate for Māori peaked at 25.6% in 1992 and 27.5% for Pacific People in 1991 (see figure 1). For young people aged 15–24, the unemployment rate reached a peak of 19.1% in 1991 (MSD, 2016).

A line chart shows yearly rate, by ethnic group from 1986 - 2014 for Unemployment rate. There is a break in ethnic defintions from 2008, people can be counted in more than one ethnic group (total response).

________________

One of the lessons from the reforms of the 1980s and early 1990s is that persistent long-term unemployment was particularly harmful (Nolan, 2013). In 1987, unemployment was low and the proportion of people unemployed who were out of work for 6 months or more (long-term unemployed) was only 27%. However, by 1991, 44% of people out of work were long-term unemployed. Even in the good times, long-term unemployment amongst disadvantaged communities persisted. This proportion remained above its 1987 level until 2003, because employers were relatively unwilling to take a chance on people who had been out of work for a sustained period (Nolan, 2013).

From 1991, social assistance became targeted and more conditional. Assistance became targeted to those on very low incomes. The 1991 cuts to entitlements were substantial for most benefit categories[5]. The new benefit levels were set in relation to an ‘income adequacy standard’ that was based on estimates of minimum requirements for food and living expenses. This estimate departed from the principle of relativity that had guided government policy since 1972. Policy reforms through the 1990s focused on reducing benefit ‘dependency’ and moving benefit recipients into paid work.

This period saw the emergence and expansion of increasingly targeted supplementary assistance programmes on top of the basic benefit to meet a range of individual needs[6] (Mackay, 2001). In the 1990s, supplementary payments were reformed. For example, housing assistance provided through the new Accommodation Supplement was intended to target expenditure on housing support more tightly to those most in need[7]. Together with lowering of the levels of the main first-tier benefits, changes to supplementary payments resulted in a large shift in the balance between the amount of assistance delivered through the basic benefit and the amount delivered through the second-tier programmes. In 1984, spending on second-tier assistance amounted to only 1.1% of total expenditure on benefits and pensions but, by 1996, this had increased to 9.4% of the total (Mackay, 2001). The system of supplementary payments, developed on an ad hoc basis rather than being based on empirical evidence, is complex to administer and difficult for staff and end users to understand. Take up of the supplementary payments is lower than expected, especially among people who are not receiving first-tier assistance.

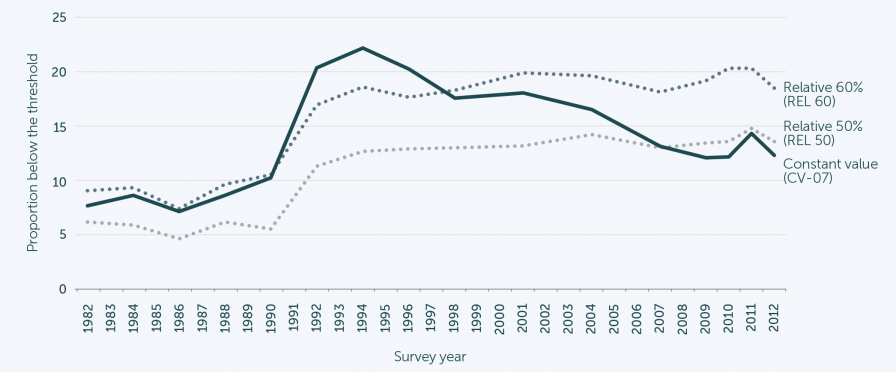

Financial hardship increased for many New Zealanders in the 1980s and 1990s. This can be seen with the emergence and expansion of food banks (Mackay, 1995; 2003) and increased poverty rates (see figure 2). In response, the Government introduced greater requirements on benefit recipients to use budgeting services.

A line chart shows yearly survey from 1982 - 2014 of the proportion of population with net-of-housing-costs household income below selected thresholds.

________________

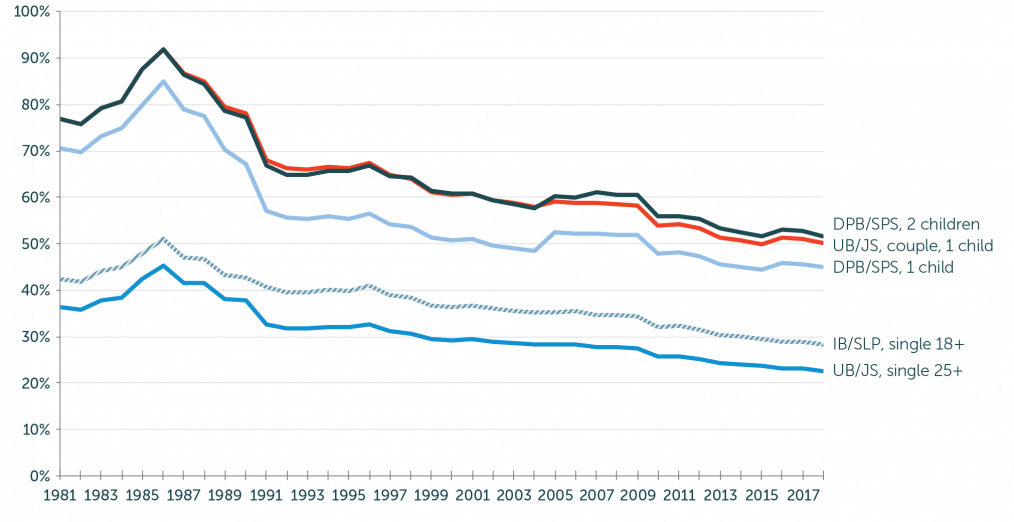

After 1991, main benefit rates (but not supplementary and other payments) were adjusted annually for changes in the consumers price index. They were not, however, adjusted in line with changes in wages or incomes. The result is that the incomes and living standards of benefit recipients have continued to fall behind those of the rest of the community. This is clearly evident in figure 3, which shows the trend since 1981 in after-tax benefit rates, including family assistance, as a percentage of the after-tax average wage.

Source: Fletcher 2018a.

Notes: DPB = Domestic Purposes Benefit; IB = Invalid’s Benefit; JS = Jobseeker Support; SLP = Supported Living Payment;

SPS = Sole Parent Support; UB = Unemployment Benefit.

Family assistance includes Family Tax Credit, Family Support, Child Supplement and Family Benefit over the relevant years. It does not include In-Work Tax Credit or any partial entitlement to Family Tax Credit a person/couple on the average wage might be entitled to. Average wage is all industries, both sexes, average ordinary earnings (FTEs).

A line chart shows a comparison of benefit rates to average wages from 1981–2018. This shows a steady decrease from 1985 until 2017 in Domestic Purposes Benefit/Sole Parent Support, 2 childern, Unemployment Benefit/Jobseeker Support couple, 1 child, Domestic Purposes Benefit/Sole Parent Support, 1 child, Invalid’s Benefit/Supported Living Payment, single 18+ and Unemployment Benefit/Jobseeker Support 25+.

________________

The changes to the welfare system in the 1980s and 1990s did not happen in isolation. Increased targeting across health,[8] education[9] and the benefit and tax credit systems resulted in overlapping withdrawal of state assistance with increasing income. This created the potential for poverty traps where people lost more income than they gained from increasing their earnings from work (MSD, 2018a).

The most recent changes, in the period from 2010 to 2017, did not alter the rate of most benefit payments[10]. They sought to make the rules and administration of welfare more ‘work focused’, with changes in benefit names, a wide range of new obligations and conditions and an emphasis on reducing numbers on benefits using targets and other key performance indicator measures. The changes also sought to target more intensive assistance and case management towards those benefit recipients likely to cost the most in terms of future benefit expenditure (for example, sole parents) and away from benefit recipients who were likely to quickly move into work (for example, new job seekers)[11]. These changes have reduced total benefit numbers (aided by a strong labour market), which fell from 320,041 in June 2012 to 276,331 in June 2017[12]. No evidence exists that the changes improved the Ministry of Social Development's (MSD’s) effectiveness in placing people into employment or resulted in an overall improvement in incomes and wellbeing for current and past benefit recipients.

The rate of ‘churn’ of people going into unsuitable or precarious work for short periods then back into the benefit system shows many people were experiencing few positive and long-term changes in their wellbeing. A recent study found that close to one out of every two people leaving benefit returns within 18 months, especially those with lower earnings (Judd & Sung, 2018).

The historical trends in the welfare system are consistent with what we heard in our consultation hui. An overwhelmingly common theme throughout the consultations and in written submissions was the wholly inadequate nature of current levels of income support. Associated with these concerns were comments about housing costs, debt and increasing rates of homelessness (Johnson et al, 2018). In addition, the financial incentives to enter paid employment are minimal once benefit abatement rates and thresholds, taxes and work-related transport and childcare costs are accounted for.

"The current welfare system is inadequate and children and whānau are missing out on necessary things such as food and power. Sacrifices are being made and this is impacting on our children. Hungry children cannot learn at school and these children are the most at risk of future negative outcomes. Whānau are stressed and becoming overwhelmed."

PAST WELFARE RECIPIENT

These points are supported by evidence from our construction of budgets for a selection of example families. We found evidence that the levels of main benefits are well below those levels necessary for an adequate standard of living, let alone the levels necessary for even modest participation in society. Even with modest levels of expenditure across core spending items (for example, food, power and housing), individuals and families receiving a range of income support payments face ongoing financial deficits (total spending levels greater than their income entitlements). These conclusions also hold for many of those in paid employment on low wages. Further, spending that allows people to participate meaningfully in their communities (for example, children’s sports fees) results in even larger deficits, as does servicing existing debt. Our findings from the example budgets analysis are detailed in chapter 7.

As a result of benefit levels being below the level required for sustaining even a basic standard of living, many people receiving benefits are in debt. The combination of unsustainably low incomes and high basic living costs means indebtedness is almost inevitable for many people on benefit for any length of time. The growing debt burden becomes a vicious circle, resulting in even less disposable income as families struggle to repay debts, including recoverable grants from MSD. Debts to third-tier lenders usually involve high interest rates, high fees and high penalties for late payment.

One of the largest expenses people face are housing costs. On average, housing costs make up around 45% of expenditure for low-income households. For the bottom 20%, average housing costs as a proportion of average income have increased from 29% to 51% since 1988. Housing affordability is an important contributor to wellbeing and a reasonable standard of living. Home ownership rates have fallen to their lowest rate since 1953. The rate for Māori households declined 20% from 1986 to 2013, while for Pacific households the decline was 35%. Māori home ownership is around 28%, Pacific 19% and European 57% (Johnson et al., 2018, WEAG, 2019i). At the same time, renting has become less affordable, leading to overcrowding, and homelessness is a serious problem.

"[We are concerned about] housing and lack of suitable housing, children and families in emergency accommodation long term."WELLINGTON ROUNDTABLE

There are just not enough houses to meet demand. Of the current housing stock, too many are unaffordable for low-income families. Many are substandard, poorly insulated, damp and unhealthy. A critical longer-term aspect of the housing crisis is its contribution to the growth of wealth inequality: a central aspect of our original welfare system was the ability of most people, including low-income families, to acquire an asset base in the form of a house. The policy was effective in reducing poverty in old age because most households paid off their mortgage before retirement (Castles, 1985). We now face the prospect of a large cohort of renters who will become superannuitants, moving into their later years without housing security and with the ongoing cost of rent payments.

The housing crisis is also a critical issue contributing to ill health, with the above factors causing stress for those who are unable to live in a secure, warm, dry home of the right size for themselves or their family. Numerous studies into the health of populations and their housing conditions provide evidence of strong associations between poor health and low-quality housing (Howden-Chapman et al, 2012; Howden-Chapman & Chapman, 2012; Mueller & Tighe, 2007; Thomson et al, 2009).

Overcrowding increases the risk of infections spreading, including life-threatening diseases such as pneumonia and bronchiectasis, asthma attacks, gastroenteritis, serious skin infections, kidney diseases, rheumatic fever and meningococcal disease. Coldness, damp and mould increase the risk of getting sick with a virus, makes asthma worse, and can increase the incidence of heart and lung disease. Living under financial stress in poor-quality housing or no housing is a contributory cause and consequence of mental illness (Government Inquiry into Mental Health and Addiction, 2018; Potter et al, 2017). Census data consistently shows that Māori and Pacific People are much more likely to live in poor-quality housing and face these higher health risks.

Various aspects of the welfare system work against people building up assets. Housing support for rents or mortgages has harsh asset-testing rules that make it difficult to become a home owner. The state could end up paying much more in housing assistance than it would have had it supported households into their own housing. Housing for disabled people is frequently not modified for their needs. Multi-generational Pacific families seldom have houses large enough to cater for them and end up overcrowded, even though building separate smaller houses is much more expensive than building a larger house on a square metre basis.

The social contract[13] is evident in key New Zealand statutes such as the 1938 Social Security Act. Government provision of financial assistance for New Zealanders unable to achieve an adequate standard of living was central to the social security system set out in the 1938 Act, alongside other critical support such as access to health care, education, housing and adequate employment. On the other side of the contract, there are expectations of people receiving financial support, such as an expectation to participate in training or other activities or to seek employment where appropriate.

"Often those on a benefit are at the LOWEST point in their lives and they need encouragement and acceptance from Work and Income case managers. They don’t need to be pulled lower but need to be pushed higher and supported generously. I think case managers should go through more training on social services and how to relate to people that are dysfunctional and need their help. Compassion! Support your clients with compassion."

PAST WELFARE RECIPIENT

While the social security system has undergone periods of significant reform (as mentioned earlier), the broad consensus throughout our consultation is that it is the Government’s responsibility to provide that support. Since the 1980s, the support provided to people by government has been reduced. Requirements that must be met, and aligned sanctions, to access the reduced support have increased considerably and contributed to the hardship faced by many in the welfare system. In our view, the social contract has become imbalanced.

The current benefit system is based on a one of conditionality and sanctions. We heard overwhelmingly through our consultation that such a system diminishes trust, causes anger and resentment, and contributes to toxic[14] levels of stress. The application of obligations and sanctions in New Zealand (and elsewhere) is problematic.

Work obligations have always existed in the social welfare system. The emphasis on work obligations has increased over time, and this increase has included the expansion of full-time and part-time work obligations to more people, with requirements to participate in work-preparation activities for almost everyone who is not subject to a work test. However, most of the obligations under the current regime are not work related, instead they are designed to elicit certain social behaviours or to transfer some administrative burden to the recipient (MSD, 2019a).

The empirical literature provides no single, overarching answer to whether obligations and sanctions in welfare systems bring about the desired forms of behavioural change, such as movement into paid work or whether the positive effects of obligations outweigh the negative (Watts & Fitzpatrick, 2018: 111). Research does indicate that obligations and sanctions can be costly to administer and comply with and have many harmful unintended consequences that compound social harm and disconnectedness (for example, movement in and out of insecure jobs, interspersed with periods of unemployment; disengagement from the social security system; increased poverty; increased crime to survive; worsened ill-health and impairments) (Economic and Social Research Council, 2018; Watts & Fitzpatrick 2018; Butterworth et al, 2006; Kiely & Butterworth, 2013; Davis, 2018). There is even less evidence that non-work-related obligations and associated sanctions achieve the stated aims of intended behavioural modification.

A high number of obligation failures[15] are disputed (46%) and almost all (98%) of these disputes are upheld with the failure being overturned. This may indicate that the disputes process is working effectively, but it also highlights that, often, failures that can lead to sanctions are applied incorrectly and without the proper checks being applied (MSD, 2019c).

This environment has contributed to people losing trust in the service they have been receiving. People consulted reported that aspects of MSD’s operation that eroded trust included:

Recent research recommends a move away from such systems towards more personalised services.

Many people on the consultation talked about the value of advocacy in relation to having support at their interviews, as well as the value of being able to get information about their entitlements. Some MSD staff also commented on how useful and helpful advocates often were in interviews and other interactions. Advocates are often volunteers in their communities or are community workers doing multiple support roles with different agencies, and this vocation needs to be supported by MSD staff and management.

"I have often been to WINZ [Work and Income, Ministry of Social Development] appointments with people on a benefit. The beneficiaries usually get terribly stressed for a week or so before the planned appointment. It shouldn’t be a stressful experience. Some staff are wonderful and know what the beneficiaries are entitled to, the next WINZ staff member that the beneficiary may see, may tell them something entirely different – it is very confusing and feels like a roller coaster ride."FRIEND/FAMILY MEMBER OF WELFARE RECIPIENT

________________

Last modified: